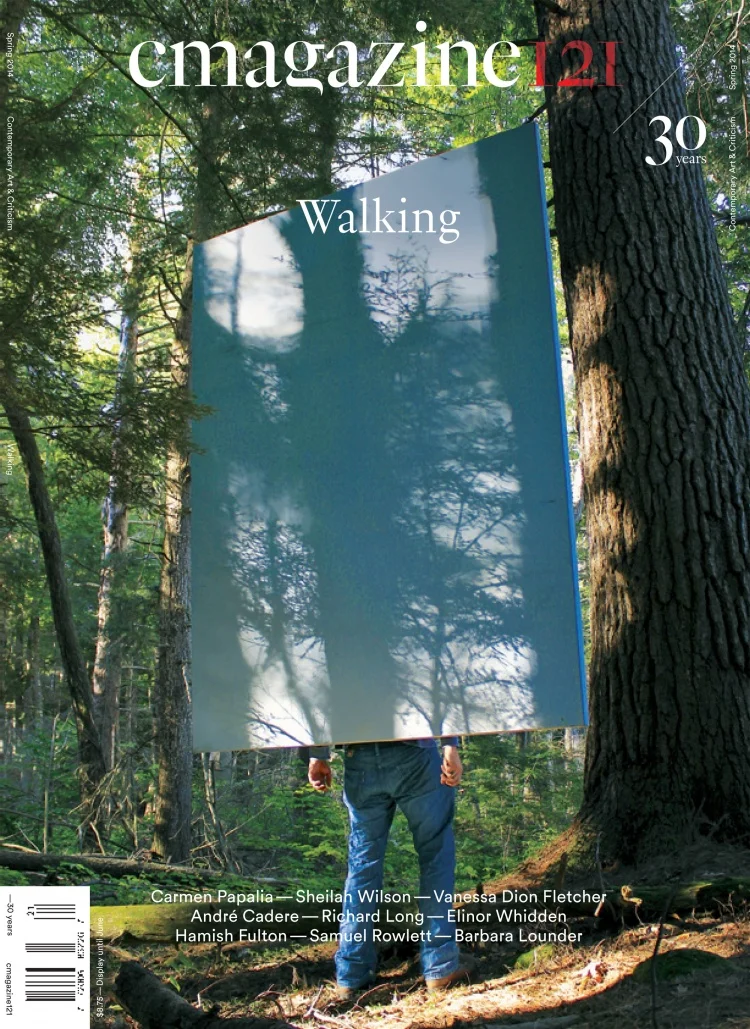

C Magazine Issue 121: Walking

View full issue here.

C Magazine Issue 121: Walking

Spring 2014

Walking

In this issue we look at the work of artists who use walking as their medium. Recently there have been numerous exhibitions, publications and research projects that deal with walking as an aesthetic practice. This focus is nothing new: walking has been a staple of art practices since the 1960s — in sculpture, conceptual art and, more recently, social practice. In fact, throughout history, countless writers, philosophers and artists have used walking to explore and describe a relationship between movement and thought. Writers ranging from William and Dorothy Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Henry David Thoreau and Charles Baudelaire to Robert Walser; philosophers including Jean–Jacques Rousseau and Walter Benjamin; Dadaists and members of the Situationist International; and contemporary artists including Stanley Brouwn, Trisha Brown, Janet Cardiff, Lygia Clark, Hamish Fulton, Richard Long and George Macuinas — among innumerable others — have all employed walking as a shaping force in their work. And, to look further into the past, walking was an integral part of the teaching of philosophy in ancient Greek society.

But why look at walking now? Arguably walking practices are emphasized when there are significant transitions in how the body senses and moves through the spaces it occupies. During the 18th century, as the middle and upper classes began to travel increasingly by horseback and coach (and later by trains, cars and by air), writers such as Wordsworth saw new forms of travel as immobilizing the body and separating us from one another, reflecting the Romantics’ rejection of scientific rationalism and their emphasis on having a direct connection with nature. For Wordsworth, and for others of his time, walking came to be seen as representative of bodily and intellectual freedom, and expressive of a politics where the politically disillusioned could share common ground with the economically disenfranchised.1 Two centuries later, in the early decades of the 21st century, sensation and movement have become increasingly directed by new kinds of infrastructure both real and virtual. Transportation networks and technologies circumscribe physical movement in increasingly complex ways, and web–based technologies such as email and social networking programs now govern our movement through virtual space. By emphasizing bodily experience, and sometimes using these very technologies, walking practices evoke a similar critique of how the relationship between the body and space is configured in contemporary society.

Physical spaces are also being transformed through the construction of communication and transportation infrastructure; for instance, the extraction of resources needed to maintain these systems results in the destruction of ecosystems and the dissolution of memory. Specific places become destinations for leisure or tourism where walking is the predetermined activity. In contrast to the 18th and 19th century, 1st century walking is increasingly an activity of the well–to–do, who are more likely to have both leisure time and access to walkable places. The walkability score of a neighbourhood, which can be checked online by entering one’s postal code, also affects property values. Amidst these changes, it is urgent that we consider how we occupy the spaces around us, and how movement structures and shapes our relationships to others.

The artists in this issue offer an embodied critique of these new spatial conditions. Many of them employ walking as “walking with,” such as those featured artists who evoke Canada’s past and ongoing treatment of First Nations cultures, for whom walking is both an evocation of memory and a political action, engaging the complex historical and cultural conditions that shape our experience of the land itself. Some artists in this issue use walking as a way to open up their non–ocular senses, finding ways of knowing and communicating in the absence of the visual. And others employ walking as a form of play that aims to discover new ways of engaging with public space.

As the contributors to this issue reveal, walking is a way of re–inhabiting the spaces we occupy, and finding new ways of relating to those with whom we share it. As we move through space, we let space move through us, feeling the land and its memories in our muscles and bones. And, most importantly, these are shared spaces, where we walk with others, where audience members are also collaborators, and where, together, we create our own landscapes.