View full issue here.

C Magazine Issue 116: Collections

Winter 2012/2013

Collections

The impulse to collect is one shared by artists and patrons of art alike. The gathering and organizing of ideas, experiences, objects, words and/or images forms the basis of every artist’s work. The art collector has a similar commitment, engaging with artists’ material outputs reflectively and sympathetically, thereby participating in the experiences and ideas they conjure. When it comes to contemporary art, both artist and collector are unified in reflecting upon and trying to understand what it means to be in the world today.

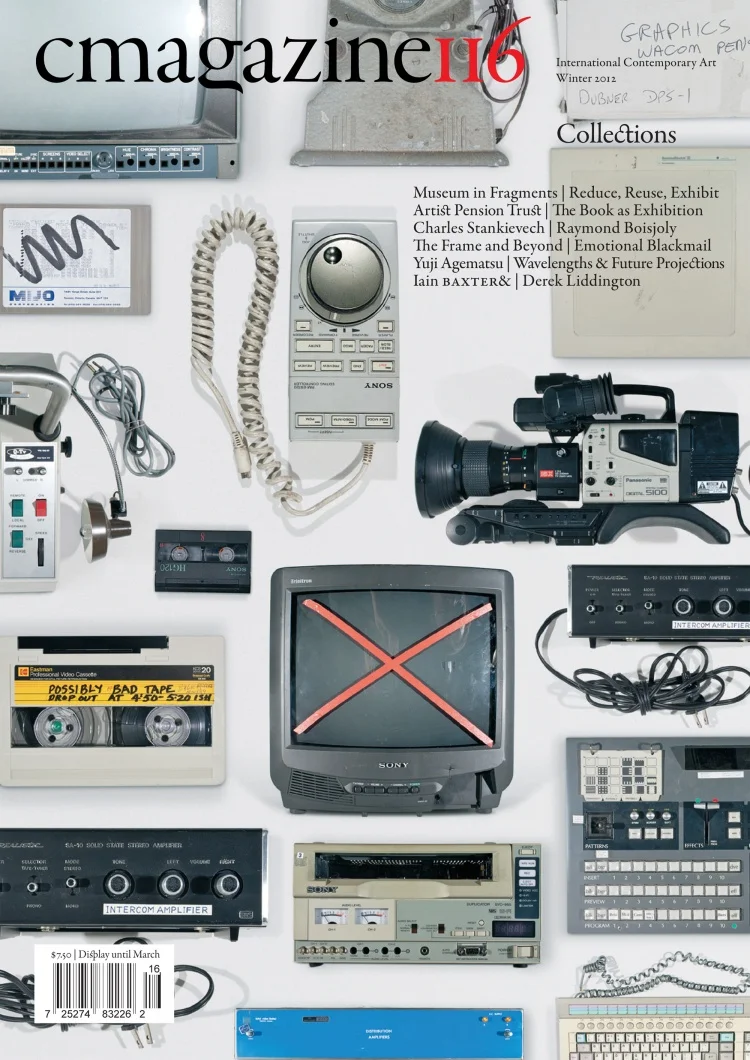

In this issue, we examine the artist-collector, who organizes and curates objects as part of his or her material output, and the patron-collector, who is motivated by pleasure, curiosity, and sometimes financial speculation. Complementing an artist project by Charles Stankievech, Pandora Syperek writes about that artist’s works made in the far North of Canada and in Marfa, Texas, which explore the Cold War era, Minimalism and Modernism through an engagement with artifacts from popular culture, modern art and design. Engaging similar methods for dealing with the presentation of cultural texts and objects, Sophie Springer surveys a number of book works and considers how they operate as mobile and inexpensive exhibition spaces through which collections of artworks, objects, images and ideas can be curated. Also on the theme of the artist as collector, Laura Kenins writes about artists who create sculptural installations using outdated media, including record albums, VHStapes, discarded computers and hospital equipment. Theseartists work as collectors, curators and editors, often placing already-existing images or objects into new formal arrangements.

Exploring the much less visible realm of the patron-collector, Randy Gladman writes about the philosophy of Toronto-based collectors Alison and Alan Schwartz. While private collections such as theirs are shaped largely by individuals’ aesthetic curiosities and their interests in specific artists, other collections are shaped entirely by financial speculation. On the topic of art as investment, Shannon d’Avout d’Auerstaedt writes about the recently created Artist Pension Trust, discussing its data aggregation software model that predicts financial returns on works by contemporary artists, and exploring its role in shaping the kind of work that may ultimately be produced.

Collecting contemporary art is uniquely complex. Most works aim to challenge viewers to think, feel and understand in unfamiliar ways, and consequently lack many of the familiar codes that would otherwise make pieces more widely accessible. And for collectors interested in art that is likely to increase in value, it is difficult to predict which artists will acquire the level of professional and commercial success needed to guarantee a return on investment. But for those who are excited about the possible ideas and experiences that contemporary art offers viewers, it’s a highly accessible realm. Artist-run centres, as well as public and commercial galleries, present living practices that are also sited in an active public discussion. This occurs at openings, through talks and exhibition tours, through reviews and myriad other forums. For the patron-collector, such art is much more affordable than art that has already been tested by the market, and contemporary art offers an experience that is far beyond purely economic valuation.

In this issue, the artist, collector, curator and editor share similar roles in organizing and interpreting the objects and texts (and detritus) of contemporary culture. Such material always needs to be framed and supported. Responding to a persistent problem at the Donald Judd Library in Marfa, Texas, where passing trains cause books to vibrate out of place, Charles Stankievech presents a bookend he designed for Judd’s library as this issue’s artist project. While it can never be put into use because Judd’s instructions stipulate that his library remain exactly as he left it, like a room, a book or a magazine—or, for that matter, the mind of the collectors themselves—it can still serve as an apt metaphor for the deliberate containment that a collection requires.