See full issue here.

C Magazine Issue 111: Libraries

Fall 2011

Libraries

For many of us, the context in which we encounter a book or a reading, and the community of readers with whom we share it, is often as important as the text itself. I find it difficult to conjure from memory the contents of a book without being able to recall where I read it, what I was feeling, the people around me, and other things that might have distracted me at the time. For all of us, these peripheral, affective experiences are essential to how we make sense of and incorporate what we read and how we recall it later. For example, I can’t think about Brillat-Savarin’s The Physiology of Tastewithout also thinking about the small town on the side of a volcano in Sicily where I read it. It reminds me of honey, pistachios, porcini mushrooms, spring snow and the Ionian Sea. I can’t think about any of the essays from Walter Benjamin’s Illuminations without also thinking of all the courses in which I’d read them as a student, or my own courses in which I’d taught them, or the many people with whom I’d discussed their ideas. Books that I read in my childhood or novels I’ve read recently evoke even more powerful memories and associations. The books read over the course of a life constitute an elaborate index of places, memories and communities, both describing and enacting a world read through their authors and their ideas, where the substance of the text and life of the reader are intricately woven together.

For these and other reasons, the spaces in which we engage texts, and how we physically interact with them, deserves special consideration. I always carry a book with me in hopeful anticipation of finding the right time and space to enjoy it, and I leave books in places where I think they might best be brought to life. While editing this issue, I found myself walking through the night to a collection of books kept in a cabin in the woods, where I sometimes stay. This small library includes, among other titles, an 1894 edition of short stories by Tolstoy, a book called The Indian Tipi, a 1950 research study titled Folklore of Lunenburg County, a rhyming dictionary, a cultural history of attitudes towards night, and an 800-page guide to lichens. I keep these books especially for this place.

This issue proposes taking thoughtful pleasure in acts of reading as well as in the spaces where we collectively engage with texts: where we gather them, share them and read them. In her article Soft Protocols, Jen Hutton writes about the work of Dexter Sinister and their current project, The Serving Library, in terms of how they take up many of the material and social aspects of our engagement with print culture and invite a slow and immersive engagement with the processes of creating and reading texts. She notes that there are many texts where their value is based simply on their presence—which unfortunately happens all-too-often in academic or online publishing. Without a reader and a context to inhabit, a text is not complete—it doesn’t have any meaning or action upon the world. However, Dexter Sinister aims to create a context in which the contemplation and dialogue that’s essential to the meaning of a text can occur.

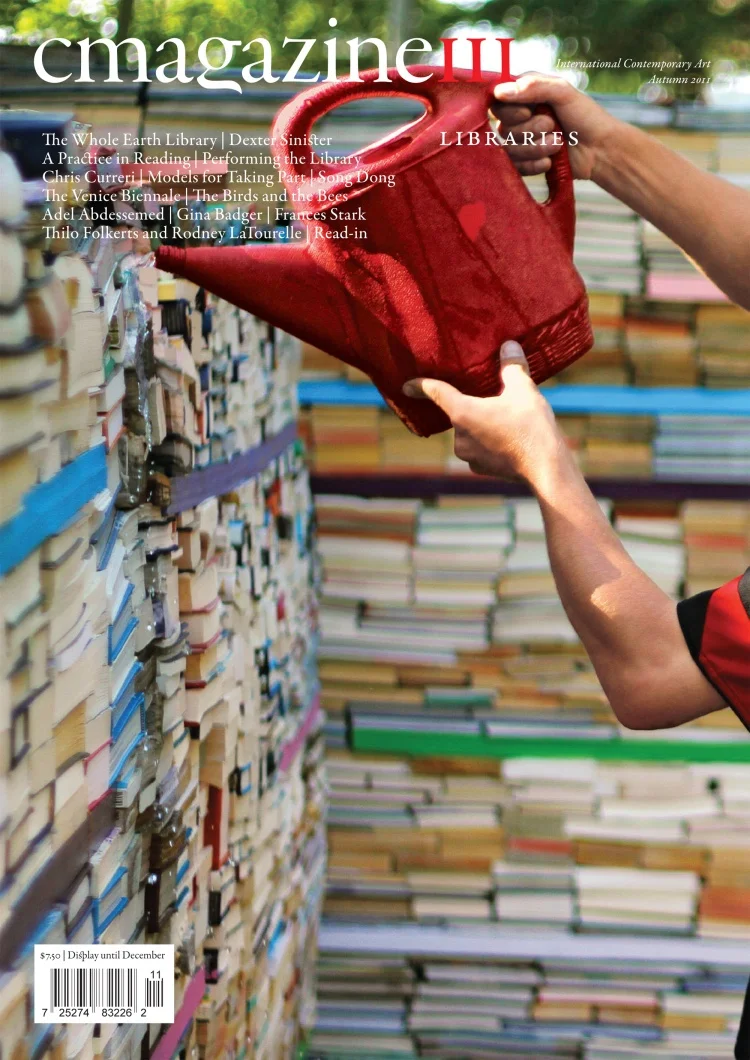

In Performing the Library, Adam Lauder looks at works by a number of contemporary artists who stage different kinds of libraries, engaging—sometimes through physical movement—the formal structures through which knowledge is organized and disseminated, often creating new connections between texts and between different political histories and communities. Lauder’s essay also deals with the idea of obsolescence, which has particular resonance as online texts replace printed pages, making increasing amounts of printed matter available as source material for artists. One particularly poetic use of discarded books is illustrated by Jardin de la Connaissance(2010-11), an installation by Thilo Folkerts and Rodney LaTourelle, who collected approximately 40,000 books, configured them into walls, rooms, benches and floors, and then inoculated them with the spores of eight different species of mushrooms. Installed at Les Jardins de Métis in Grand-Métis, Quebec, the books became part of the landscape, exposing their ephemerality as they decomposed. While the artists describe this project as being about the relationship between knowledge and nature, it also evokes an awareness of the potential obsolescence of ideas and the forms by which they are stored and communicated. There is an enormous volume of books that are produced and discarded, or read and forgotten, that over time lose their purpose and value.

In this issue, Read-in Manual, an artist project by the Read-in collective, explores the social and political dimensions of reading. Here, members of the Read-In collective propose the formation of groups of readers who solicit a stranger to allow them to create an informal reading group in their home and collectively read a text that responds to this particular space. In a different way, Randy Lee Cutler’s article A Practice in Reading explores the phenomenological experience of reading and how reading books has unique physiological qualities and spatial-temporal dimensions that distinguish it from the experience of reading digital texts. Cutler argues that we need to pay attention to the embodied experience of reading, and she invites us to consider reading as a practice like yoga, meditation or music. The practice of reading has changed considerably over history. For example, Cutler writes that silent reading didn’t become commonplace until about the tenth century, corresponding with the idea that reading allowed one to inhabit a reflective, interior space where the text could be more easily inflected by one’s thoughts and memories. With the wide availability of texts online, reading has become more fragmentary, associative and increasingly social, where one follows particular ideas through hyperlinked articles and Google searches, commenting on things they have read and sharing them with others, without necessarily having read and reflected on the entirety of an article.

Libraries serve not just as spaces in which to house and organize knowledge about the world, but also to bring particular communities and ideas to life. In The Whole Earth Library, David Senior surveys the history of The Whole Earth Catalog, a directory of tools and sources of information about sustainable living published in various editions during the late 60s and early 70s. Senior begins with a proposal made by its editors, by building a library assembled from many of the books it describes. The Catalog was in many ways a compendium of what were, at the time, seemingly obsolescent ideas, but which gained critical currency as part of the back-to-the-land and environmental movements that were taking shape at the time. Despite this, the catalog is remarkably forward thinking, in prefiguring the Internet by describing a new global consciousness shaped by ecology, communications theory and cybernetics, and operating as a hub for DIY culture. Like many of the writers and artists in this issue, this piece describes the co-evolving relationship between nascence and obsolescence, decay and regeneration, books and the worlds they describe, and libraries and those who bring them to life.