View full issue here.

C Magazine Issue 128: Citizenship

Winter 2015/2016

Citizenship

AM: When we began work on this issue, last June, Canada’s Bill C-51 “Anti-terrorism Act” had just been passed, enhancing the government’s powers of surveillance, along with a new provision to Bill C-24, the “Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act,” enabling the federal government to revoke Canadian citizenship from dual-nationals. At the same time, a Conservative government was making it increasingly difficult for refugees to find asylum in Canada, all of which was happening within the context of the Syrian refugee crisis and daily reports of people drowning while crossing the Mediterranean. Just weeks earlier, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report was released, detailing the mechanisms and effects of cultural genocide that were enacted through Canada’s residential school system as part of the creation of the Canadian nation state.

KC: An art magazine issue on citizenship will necessarily be inadequate and incomplete, and this recognition followed us through the editorial process. Throughout we questioned how to explore citizenship not as a “current topic in the art world,” or something to make work “about” – but as a question affecting us all; as citizens beyond nationality and background; as embodied subjects, with our histories, communities and varied positions of power. A question that – given the current events described by Amish above – yields few answers. We proceeded in conversation with artists, writers and our editorial advisory board, who in turn invited in more voices and new writers; in an attempt to diffuse the position of the editor as gatekeeper or arbiter, however impossible this might be.

AM: One of the things that came out of our discussions with members of our advisory – including some who had been to this year’s Venice Biennale, was the fact that it was thematically framed as responding to current global crises, and the conditions of migrant labourers and refugees, yet it firmly positioned some kinds of people outside of the Biennale. In response, we commissioned a number of writers and artists who were in attendance to address this contradiction and discuss specific interventions into constructions of nationality at the Biennale. In many ways, doing so seemed to get at a larger discrepancy within the art world where we traffic in the critique of conditions of inequality and exclusion, while these same problems aren’t merely present in the art world, but magnified. C Magazine isn’t entirely innocent of these contradictions either. But one of our jobs is to call them out, and to give space to writers and artists who can help us think through them in productive ways.

KC: If we continue using the Venice Biennale as a marker for one of the most public ways in which citizenship or the nation-state shapes the perception and valuation of art, we should consider artistic director Okwui Enwezor’s prologue to this year’s exhibition: “The principal question the exhibition will pose is this: How can artists, thinkers, writers, composers, choreographers, singers, and musicians, through images, objects, words, movement, actions, lyrics, sound bring together publics in acts of looking, listening, responding, engaging, speaking in order to make sense of the current upheaval?” Do we react? Do we carry on, with the belief of art as a universal good in the face of a chaotic world? Who has the privilege?

AM: One of the questions that arose as the issue came together was how do we talk about these problems when C’s staff is made up entirely of people whose citizenship is almost never questioned. We saw the risk of reproducing this false neutrality, where citizenship was presented as always concerning an “other” whether on the basis of race, nationality or sexuality. It became increasingly apparent that we needed to interrogate many of the different ways citizenship is produced, both consciously and unconsciously. In this issue Yaniya Lee looks at this idea of neutrality within art criticism, and at instances where it serves to re-inscribe forms of exclusion and reaffirm dominant forms of citizenship. One of the ways we are implicated as editors and writers is through how we frame and represent other peoples’ words and ideas, so we are faced with the question of how not to project our own assumptions and experiences on others, and instead learn to listen and converse.

In the spirit of this conversation, we invited artists and writers to respond to the Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a document that is 536 pages long and includes 94 calls to action based on 6,740 statements, including visual art, gathered over six years. We were interested in understanding what bearing the report might have on visual art practice and what ethical imperatives it might present in terms of recognizing forms of citizenship outside the national narrative.

KC: If we continue to ask: How do you think and write about art in the midst of a global crisis? How do you think from within a country geographically isolated and often self-satisfied, able to continue on with daily life, and yet still implicated in other more long-standing betrayals of citizenship? I need to think, in this case, not of the dominant art world’s glossiness, commerce and object fetishization, but of art as a historically rooted language; one that has for centuries come before words, or when there are no words. That the TRCreport accepted visual art as a legitimate form of response and testimonial reminds of this, and in turn we solicited artists’ responses to the report.

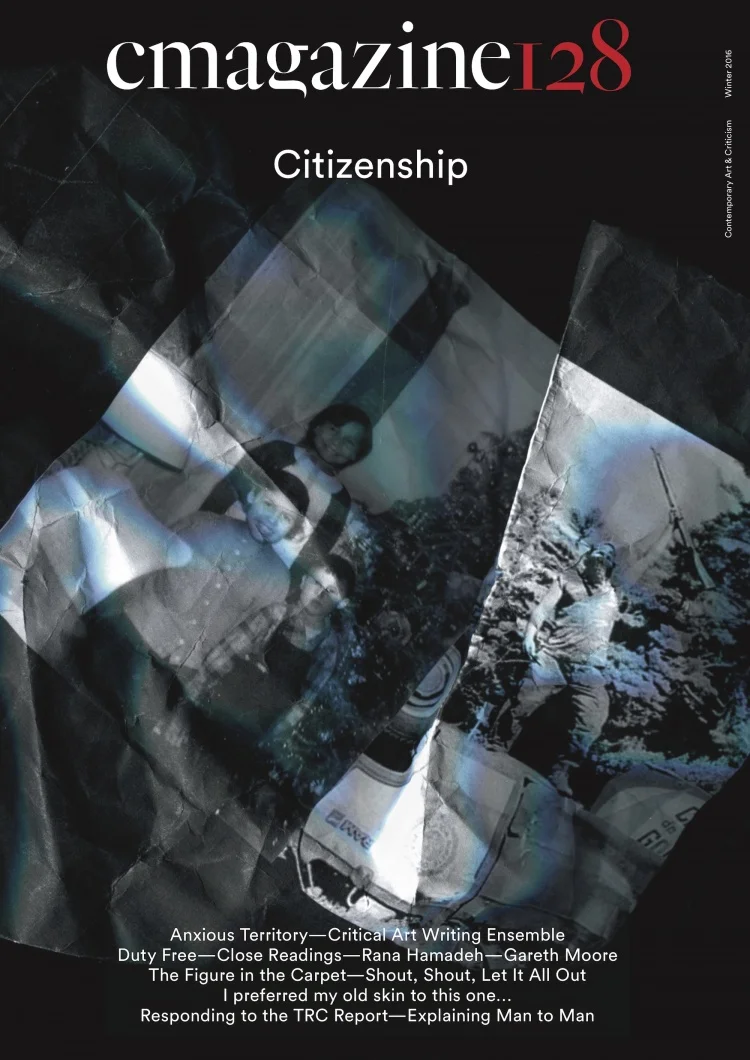

AM: Among these responses is Anishinabe intermedia artist Scott Benesiinaabandan’s marykennethagnes | oka, a photograph that incorporates an iconic image from the 1990 Oka Crisis, of a Mohawk warrior atop an overturned police car, and an image of Benesiinaabandan’s mother, who grew up in a foster home, with her siblings. Having also been placed in foster care at birth, he kept the image from the Oka uprising as a symbol of his political ideals, in lieu of family photos. When he searched out members of his family as an adult, he obtained the image of his birth mother that appears in the piece. Combined in Photoshop, printed and then crumpled into a three-dimensional form that he placed on a scanner, this image reflects a genealogy that is both visual and biological, connecting his personal history with a history of indigenous resistance.

In another article, the curator Derrick Chang addresses the position of the queer citizen-subject, looking specifically at sonic interventions into heteronormative performances of nationalism through works by Igor Grubić and Pascal Lièvre and Benny Nemerofsky Ramsay, as well by members of Pussy Riot. This reveals not only how dominant forms of citizenship are enacted through expressions of sexuality, but the ways it can also be resisted, one of which is making its workings visible. I should add that this issue of C Magazine isn’t only about citizenship as a repressive “othering” force, but about how it’s a productive force in the sense of producing conforming citizen-subjects. For the artist project Tyler Coburn interviewed workers at the Integrated Systems Operations Centre in Songdo, South Korea, one of the world’s largest urban development projects. Smart technologies are used at every level of its construction to create a system of almost total surveillance, which aims to create perfect alignment between its citizens and the needs of capital. Coburn wrote a fictional narrative, based on interviews with a worker who monitors sensor and surveillance data gathered throughout the city. Coburn’s project reveals not just how this technology produces a particular kind of citizen, but also provides poetic allusion to how these citizens might in turn intervene within or disrupt that very apparatus. In this way, Coburn’s piece speaks to the need for self-reflexivity and the need to recognize that while we may always be implicated, we also have agency.

KC: We started work on this issue just prior to the widespread attention to the refugee crisis, which intensified, shockingly, as we edited. As the issue was ready to go to press, the world sent an outpouring of support to Paris following the attacks on November 13th, which opened up a set of complexities and angry conversations over the Western world’s heedless disregard of similar attacks carried out in Lebanon and Kenya. The world continues to stratify; the pride of being a “citizen” of a desired nation-state at once increasingly loathsome and yet coveted. In the days since the shootings in Paris, a mosque in Peterborough, Ontario, was set on fire; a woman picking up her child from school in Toronto had her hijab torn off by attackers. And Canada has a new Prime Minister, who once again has pledged allegiance to the Queen of England, and whose tenure begins with hope, however wary. This issue offers many questions and few answers. It is a reminder of the ways in which we take stock of our positions, our responsibilities, the pitch of our voices in relation to others. It is a questioning of our roles as artists, editors, writers, curators and the ways in which we engage with, inherit, dismantle, disrupt and construct citizenship In our work and our institutions, without merely accepting it.