C Magazine Issue 108: Money

Winter 2010/2011

In The Money

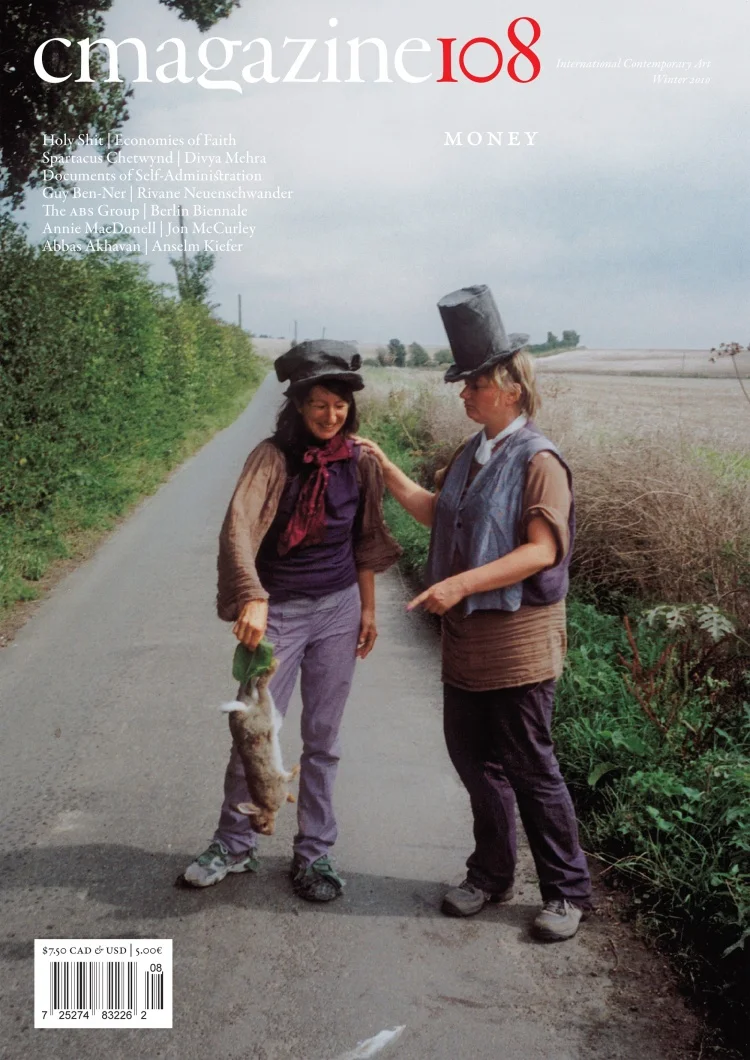

The cover of this issue depicts the artists Spartacus Chetwynd and Zoe Brown in The Walk to Dover, a film they made in 2005 in which they walk from London to Dover dressed as Victorian-era street urchins. Basing the film on the walk of the young David Copperfield, who runs away from London in the eponymous Dickens novel, Chetwynd, Brown, and a third companion, Joe Scotland, attempted to live off the land throughout their 10-day journey. Making a comparison to Copperfield, who left London to escape the brutal conditions of industrial servitude, The Walk to Dover’s creators deliver a critique of debt in contemporary society and gesture towards an impossible ideal.

This particular work, described in the interview between Chetwynd and David Lillington, reflects a utopian, anarchic spirit that underpins much of the contemporary art practice concerned with money, economics and systems of exchange. This trend has developed over the past decade—a response, arguably, to the lingering economic recession. Recently, artists Julieta Aranda and Anton Vidokle launched Time/Bank, a system for the exchange of skills that uses time as a standard measure rather than money. This subsequently lead to the creation of Time/Store, a space in New York City where one can either purchase or sell commodities, from food to electronics and art, using an official time-based currency designed by Lawrence Weiner, called Hour Notes. With participants providing services including translation, legal counsel, accommodation, offering to ask random strangers for their advice on how to finish an artwork, or hosting dinner parties, Time/Bank operates as a parallel economy for artists and cultural workers, while also being a platform for collaboration.

Creating alternate forms of economic exchange is just one way of many that artists have engaged ideas and forms related to money. Artists have also produced their own currency, created their own monetary systems, created work that uses money as an object or material, and made works that use systems of monetary circulation for their realization. There are many precedents for the work of contemporary artists who use money as part of a material and conceptual practice. In 1919, Marcel Duchamp paid his dentist with a hand-drawn cheque, to be cashed at “The Teeth’s Loan & Trust Company,” and which he later bought back at a price much greater than its face value. And in 1980, Gerald Ferguson installed a cascading pile of pennies in a gallery for a sculptural work titled One Million Pennies. (Each time the work is exhibited, the presenting gallery is required to withdraw $10,000 worth of freshly minted pennies from a bank.) Both of these projects interrogate the idea of value itself, and the processes through which it is produced and maintained.

In addition to its purely material qualities, money is a vehicle for the transmission of value and meaning—for instance, indicating belonging to a social group or honouring state officials—in addition to the economic transactions it facilitates. Hijacking and subverting this process, between 1990 and 1999 Canadian artist Mathieu Beauséjour imprinted almost 100,000 Canadian bills with the text “Survival Virus,” which gave them additional value as art objects, and which eventually forced them out of circulation. In another project transforming the value of currency, Paul Couillard and Ed Johnson pounded Canadian and American pennies until they became indistinguishable from one another in a performance called Sevenseason, enacted at the Art Gallery of Hamilton in 2003. Similarly, in Plot, Engage, Disperse, a performance they completed during Pride 2009 in Toronto, the artists imprinted triangles onto pennies, which they then distributed to passersby.

Work related to this theme also sometimes explores the relationship between commercial concerns and the transcendent or the sublime. In a recent show at Jessica Bradley Art + Projects in Toronto, Montreal-based artist Nicolas Baier exhibited an enlarged replica of a meteorite called Star (Black) (2010), made from a 3D scan of a graphite meteor found in Arizona, and Nugget (2010), created from donated gold objects that a jeweller melted and formed into a nugget. (The exhibition also included a legend with a photograph of each gold object and a brief description of its significance to the respective donor.) The price of the nugget was set in accordance with the price of gold on the New York, London and Tokyo stock exchanges on the day of sale, and the artist instructed that the same conditions apply to any future sale of the work.

There is a scientific basis to the association between gold and the otherworldly, and to the eternal, as evoked by Baier’s installation. In her essay, Marina Roy notes that gold is not created on earth but comes from other parts of the cosmos, formed through nucleosynthetic processes that accompany supernovae. The conversion of base materials into gold was a concern of medieval alchemists and part of a quest for the transcendent and the eternal, which continues to be vigorously pursued by contemporary biomedical scientists. In discussing the abandonment of the gold standard in 1971 by the US government, Roy examines the shift from a stable and inert measure of value to economies where life-forms themselves become, as she writes, “branded by capital.” Paired with Abbas Akhavan’s artist project, what is above is as that which is below… (2010), it forms a provocative consideration of the conditions of the body within contemporary economies, reconciling ideas of physical transcendence and bodily abjection. Further exploring the theme of money, Richard Ibghy and Marilou Lemmens’ Economies of Faith looks at how Mark Boulos, Melanie Gilligan and Olivia Plender expose the irrational, subjective and occult nature of the market.

However, regardless of whether money is actually part of either the form or the content of an artwork, art and money are always closely connected. Like all cultural practices, artists are in the business of creating value—and something transcendent—from ordinary, often devalued materials. None of the artists and writers in this issue, however, present alchemical solutions to today’s economic problems, but they do help us engage them in critical and significant ways. Who says art doesn’t pay?