View full issue here.

C Magazine Issue 114: Men

Summer 2012

Men

This issue takes its inspiration from many different sources: from feminists, gay men, lesbians, queers and transgender people; from those who don’t identify with these categories, such as rural women and men for whom coming out was never an option; and from people in heterosexual relationships who find ways of refusing authoritative and immutable conceptions of gender. Its purpose is not simply to understand how gender is shaped by cultural traditions, social institutions, economics, popular culture and product marketing which is no small task but also to examine how reconceptualizing gender altogether might help us to better understand and relate to one another. In fact, those individuals on the frontlines of this reconceptualization might lead us all in broadening our thinking about experience and self-expression.

To assemble the essays and artist projects that follow, we opened up our editorial-commissioning process to a wider audience, issuing a public call for contributions exploring how maleness is both performed and transformed, and how our contemporary understanding of men is informed by feminism, as well as by ideas of trans and queer identity. As a result, almost all of the feature articles and interviews in this issue reflect a critical and queer approach to masculinity. Furthermore, the majority are grounded in the idea that maleness as a social rather than as a biological category is a cultural construction that is internalized at a psychic level and that intersects with many different facets of who we are, such as our education, social class, nationality and ethnicity. Maleness is a marker of difference that inhabits an especially privileged place in relation to almost all other aspects of identity. And it goes without saying that there’s something wrong with that.

In recent decades, feminist, queer and trans artists have helped us rethink gender difference, distinguishing it from sexual difference and the trappings of biological determinism. In semiotic terms, this rethinking liberated the heavily coded signifiers of gender from the referent of sexual biology. Ensuing conceptions of gender and sexuality have opened up new forms of self expression, helped to recognize alternative family structures, expanded how we experience intimacy and sexual pleasure, enabled the formation of new political solidarities, and given rise to new identities. But even as facets of mainstream society begin embracing these ideas, the result hasn’t been simply more androgynous styles of self-presentation. Instead, we have the campy and hyperperformative embrace of signifiers of masculinity in places like drag king culture — a feature of American and Canadian nightclubs in the 1990s and early 2000s — when women perform various tropes of masculinity in order to reveal its artificiality and theatricality.1 And there is Toronto’s ongoing monthly club night Big Primpin, where a queer audience appropriates elements of straight hip-hop identity. However, the self-conscious embrace of highly coded signifiers of gender identity isn’t limited to queer subcultures. The clothing chain Banana Republic recently launched a line inspired by the television drama Mad Men that reflects the highly gendered fashions of the 60s. Or consider The Chap, a parodic British men’s magazine that espouses impeccable manners, tweed clothing and interesting facial hair, publishing articles promoting the lifestyle of the British dandy of the 30s and 40s and also staging Situationist-style public interventions. This broader rethinking of gender helps to explain why mustaches can now be worn only ironically, and also why we can publish an issue entirely dedicated to “men.”

Among the feature articles in this issue, Ken Moffatt looks at the role of shame in the formation of male identity, exploring the work of a number of artists including Kalup Linzy, Johnson Ngo and R.M. Vaughan. He draws our attention to a refusal of acknowledgement and a prohibition that shape both gender and sexuality. Moffatt’s ideas parallel an argument made by Judith Butler in her essay, “Melancholy Gender / Refused Identification, in which she analyzes the psychic formation of gender difference and heterosexual desire through the work of Freud. Stated in the briefest of terms, according to Butler’s theory, children disallowed homosexual attachment from an early age will incorporate the identity of the same-sex parent, but it comes at the expense of the ungrieved loss of same-sex attachment. Stated slightly differently, heterosexual desire is based on the repudiation of same-sex desire and, in turn, the gender of the lost object of desire is preserved as part of one’s own identity.2While the formation of gender is far more complex than can be explored here, these ideas nevertheless still help us to understand the psychic mechanism that lies at the origins of gender identity and heterosexuality, and present a possible understanding of the basis of heterosexism. In Butler and Moffatt’s arguments, prohibition and shame play important roles in shaping male gender identity and male desire.

In the interview “Gender Diasporist,” Shawn Syms talks to Tobaron Waxman about his performance-based works that involve forms of passing in terms of both gender and ethnicity, through masculinizing his appearance and also being read alternately as either Jewish or Muslim. Through his performances, which often incorporate elements of Jewish religious rituals, and through his video and photo-based work, he explores how the state produces particular gendered and racialized identities and helps rethink ideas of Diaspora. Similarly, in this issue’s artist project, which includes a text titled Shit Girls Say, and Lezbros for Lesbos, a centrefold pin-up and poster, reproduced on the inside of the back cover, Logan MacDonald and Jon Davies reflect on what it means as queer men to inhabit some of the same texts, spaces and ideas as their female peers, and also pay homage to these friends and mentors.

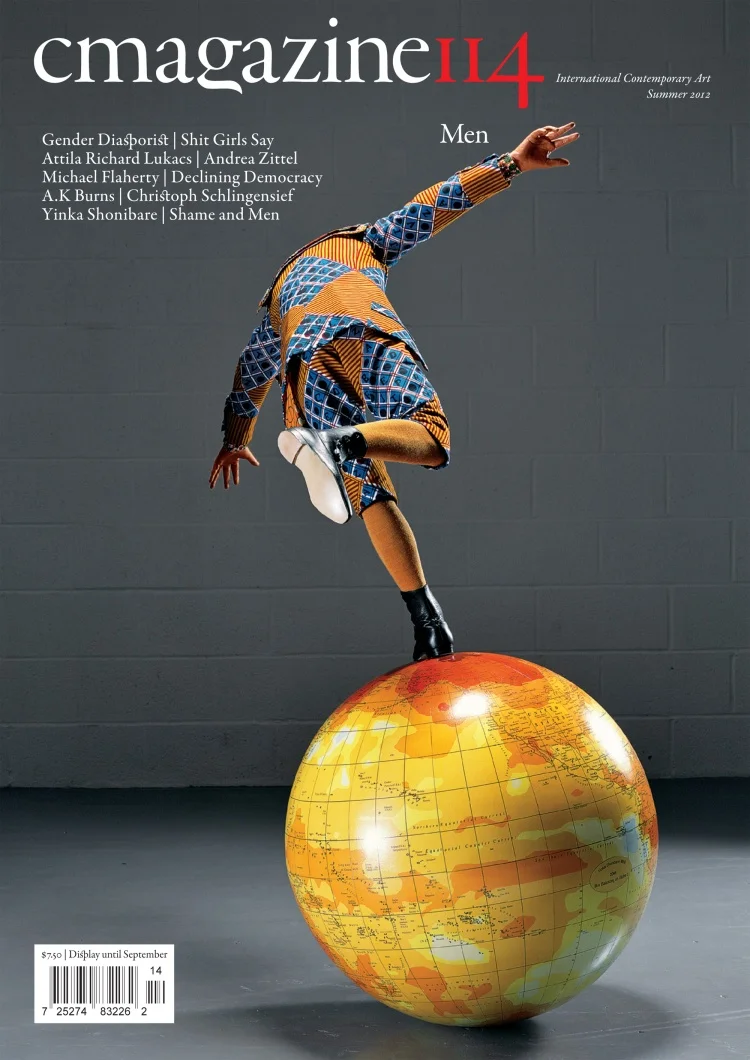

Several essays herein critique normative conceptions of male identity. In her essay on the photographs of Chris Ironside, Kerry Manders examines his photographic series Mr. Long Weekend, in which he searches for the “real man” of the Canadian outdoors. As an urban gay man, with no interest in camping, this is an especially elusive ideal for Ironside. Thus, his comic masquerade, in which he performs straight male identity by awkwardly posing in weekend campground scenarios, reveals the instability of notions of masculinity. Nigerian-British artist Yinka Shonibare, another critic of normative masculinity, discusses with Ann Marie Peña the contradictions that underlie popular representations of colonial history through the idea of the flawed hero. Referencing Shonibare’s works that often consist of installations incorporating clothing made of Dutch wax fabric associated with contemporary African identity they consider how these hybrid forms challenge a dominant global order, while invoking masculinity as part of its undoing.

The difficulty with coolly, or even ironically, appropriating elements of any identity, especially a dominant one, is the unquestioned allegiance it often requires. If we can pass as it, we also gain access to the privileges it offers. It is for this reason that our identification must never be complete: it must always hold within it something that it excludes. Our expressions of gender — whatever they may be — thus should aspire to pleasure and also to revealing our individual complexity. And while it might not always be familiar or comfortable, the negotiation of variable, contradictory and expansive identities can enact a more ethical and inclusive society.

Notes

- Judith Halberstam, Female Masculinity (Durham and London: Duke UP, 1998).

- Judith Butler, “Melancholy Gender / Refused Identification” in Maurice Berger, Brian Wallis, and Simon Watson, eds. Constructing Masculinity (New York and London: Routledge, 1995), 21-36.